Give or Take – How to build a career network that lasts

"Be nice to people on your way up because you'll meet them on your way down." Wilson Mizner

Life as a Giver

Do you ever feel like doing all the work while your colleagues seem to disappear? Do you see more patients than others or constantly fill in for your colleagues without being able to say no when someone asks for a favor? If this sounds familiar, you may have a "reciprocity style" that Adam Grant describes as a "Giver" in his book "Give and Take."

Givers are people who often give more than they receive. They are attentive to the needs of others and excel in social situations, but others frequently take advantage of them.

Takers, on the other hand, tend to take advantage of others and prioritize their own needs. In addition, they are often very smart and know exactly where the opportunities are.

In contrast, Matchers, who make up most people, believe in balance and only give when others give back.

Who wins?

You may be wondering which reciprocity style is most advantageous for career success. Surprisingly, Adam Grant discovered that the highest and lowest performers belong to the Giver category. The explanation is straightforward: some Givers occasionally establish boundaries and switch to Matchers, preventing themselves from being exploited. Conversely, purely altruistic Givers have a minimal chance of reaching the top since they are vulnerable to continuous abuse, especially by Takers.

Does the “Taker” win it all?

Does the concept of 'givers vs. takers' also apply to medicine? Who prevails, the nice or the mean? This question has always occupied me, and reading about it in Adam Grant's book 'Give or Take' opened my eyes. I remember a coworker who was a classic Taker, always finding a way to let others work for him and taking credit for their efforts. For sure, he would never do anyone a favor and often made inappropriate statements during rounds, trying to impress and brag. Although he occasionally pretended to be a giver, especially towards his superiors, his true nature was clear to his coworkers. Despite being disliked by most, he climbed the ranks quickly due to his talent for teaming up with people who could benefit him. Unfortunately for him, as he gained more power, he became more abusive and mean towards his subordinates and colleagues.

While some may argue that this goes against Adam Grant's claims in his book, the story is far from over. It may have taken years, but eventually, word of his poor reputation spread throughout the medical community, including to department heads and decision-makers. In addition, several of his former colleagues, whom he had mistreated, had risen to leadership positions. And you know what? Whenever he applied for a new job, he was always turned down. In addition, no one wanted to work with him. Interestingly, he never seemed to understand why.

The key takeaway is this: While Takers can climb the career ladder, the higher they ascend, the more pushback they will encounter. Eventually, their career progress will stall or even reverse.

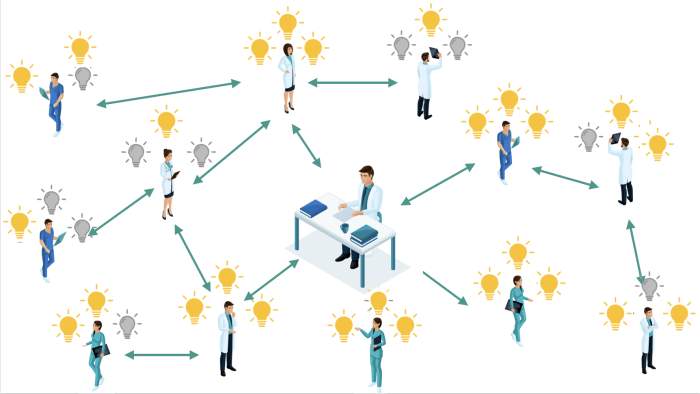

Why positive networks are important

While Givers may have a slower start in their career, they establish strong and enduring positive networks that ultimately help them to excel. Such networks may include colleagues, superiors' patients, and even individuals seemingly unrelated to the potential career. People in their network know they can expect something in return and are likelier to open up their opportunities and networks. The network size is not as important as the nature of the relationships within it: positive, neutral, or negative.

Givers are often seen as positive and reliable, and their network members may feel a sense of indebtedness that prompts them to reciprocate. This is especially true if the network people are Givers or Matchers. Importantly the higher Givers move up in the hierarchy, the more they have to give, allowing them to build an even stronger mesh. As the Giver's positive reputation spreads by word of mouth, even to those they may not know personally, more and more opportunities arise, and the Giver moves up the ladder of success, while Takers are left behind.

Added benefits and key message

In summary, it pays off to be nice. Givers who go the extra mile are rewarded, provided they establish boundaries on who and how much they help. It's crucial to genuinely mean it and also provide assistance where there's no direct benefit to oneself. Otherwise, you might be quickly perceived as a Matcher or Taker who only fakes helpfulness.

Since Givers tend to work harder and more, they usually also learn more. Moreover, beyond their careers, Givers are more likely to have more friends, greater happiness, less stress, and more job satisfaction.

Think of these benefits the next time you are "knee deep" in work and question yourself why others (the Takers) are already a few steps ahead in their career.

Thomas Binder

PS: In my next blog post, I will dig deeper into what it exactly means to build a positive network and how you can make your competence visible.

If you didn't sign up for our newsletter yet, you can do so here!

Check out the previous tips: